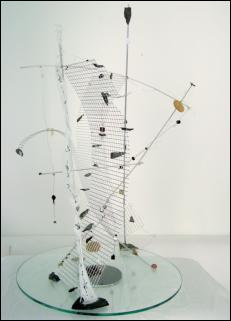

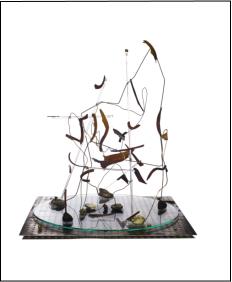

Die "folianten" sind eine Erweiterung der "graphischen Notation" wie sie in den 50er Jahren entstanden ist (Beispiele finden sich in den Arbeiten von Earle Brown, Sylvano Bussotti, Cornelius Cardew): eine Erweiterung in die 3. Dimension mit einer verstärkten Verwendung von Farbe und einem vielseitigen Gebrauch von beweglichen transparenten Materialien (John Cage hat solche Materialien bereits 1958 in "Variations I" eingeführt). Eben diese Dreidimensionalität und die Beweglichkeit sind das Entscheidende. Erstere, da sie es diesen Werken ermöglicht, im Prinzip unabhängig von jeglichen Gedanken an bekannte musikalische Notation zu bestehen (Zeichen und Bilder auf einer Fläche, die zueinander in Beziehung gebracht werden durch vertikale und horizontale Koordinaten). Zweite, da sie erlaubt, ein plastisches Konzept auf Musikalisches anzuwenden (hinsichtlich der Notation) Ungeachtet ihrer Präsenz und Eigenständigkeit als visuelle und plastische Objekte beinhaltet die Bildsprache dieser Werke viel Musikalisches. Sie verkörpern Teile von Musikinstrumenten, verdeutlicht durch die Benennung bestimmter Instrumente. Sie sind elegante Darstellungen musikalischen Materials. Und sie sind auch für einen musikalischen Gebrauch bestimmt, d.h. um Musik zu machen. Als solche werfen sie im Hinblick auf die Beziehung von Notation und Aufführungspraxis interessante Fragen auf. Wie läßt sich z.B. die räumliche Tiefe der folianten (die hinzugefügte Dimension) in musikalische Wendungen umsetzen? Wörtlich verstanden (also etwa durch die Plazierung der Klänge auf dem Klangkörper?) oder bildlich (etwa durch eine variable Klangdichte)? Oder, wie ist die Beziehung zwischen dem zeitgebundenen, linearen Charakter eines Klanges zum Raum? In welchem Sinne bestimmt eine visuell konzipierte Struktur eine akustisch konzipierte? Wenn eine ausgezeichnete musikalische Arbeit schon auf eine

graphisch unschöne Weise notiert sein kann, welche musikalische Funktion hätte dann eine anregende und anoprechende Art der Notation? Was ist die Beziehung zwischen der Dauerhaftigkeit eines Objektes und der Flüchtigkeit von Musik? Können die musikalischen Implikationen (etwa die Beweglichkeit und Zartheit von Bewegung in Zeit) dieser Werke ihnen so etwas wie eine musikalische Seele verleihen, sie sozusagen entstarren, ent-dinglichen? Die Geschichte der Notation begann als ein der Musikpraxis folgendes Niederschreiben, als Lehrbeispiel und Gedächtnisstütze und diente als Bezeichner und Erfinder einer bestimmten Art von Geschichte. Die folianten sind, paradoxerweise, sowohl Vorwegnahme von Notation als auch Rückführung auf eine ursprüngliche musikalische Praxis, irgendwie losgelöst von der Geschichte.

Christian Wolff

Kunst ist beweglich - man muß sie nur bewegen wollen. Die Folianten zeigen das deutlich. Sie zeigen Proportionen auf, die mehr in sich bergen als das, was man durch ein Schlüsselloch beobachten kann. Natürlich können wir auch eine Landschaft durch ein Schlüsselloch betrachten - und sie kann uns auch gefallen. Aber so lernen wir die große,weite Welt nicht kennen. Die Folianten können uns lehren, daß wir mehr erfahren, wenn wir die Schlüssellöcher der behäbigen

Erfahrungen ingnorieren und statt dessen die Türen selbst öffnen.

Boguslaw Schaeffer

graphisch unschöne Weise notiert sein kann, welche musikalische Funktion hätte dann eine anregende und anoprechende Art der Notation? Was ist die Beziehung zwischen der Dauerhaftigkeit eines Objektes und der Flüchtigkeit von Musik? Können die musikalischen Implikationen (etwa die Beweglichkeit und Zartheit von Bewegung in Zeit) dieser Werke ihnen so etwas wie eine musikalische Seele verleihen, sie sozusagen entstarren, ent-dinglichen? Die Geschichte der Notation begann als ein der Musikpraxis folgendes Niederschreiben, als Lehrbeispiel und Gedächtnisstütze und diente als Bezeichner und Erfinder einer bestimmten Art von Geschichte. Die folianten sind, paradoxerweise, sowohl Vorwegnahme von Notation als auch Rückführung auf eine ursprüngliche musikalische Praxis, irgendwie losgelöst von der Geschichte.

Christian Wolff

Kunst ist beweglich - man muß sie nur bewegen wollen. Die Folianten zeigen das deutlich. Sie zeigen Proportionen auf, die mehr in sich bergen als das, was man durch ein Schlüsselloch beobachten kann. Natürlich können wir auch eine Landschaft durch ein Schlüsselloch betrachten - und sie kann uns auch gefallen. Aber so lernen wir die große,weite Welt nicht kennen. Die Folianten können uns lehren, daß wir mehr erfahren, wenn wir die Schlüssellöcher der behäbigen

Erfahrungen ingnorieren und statt dessen die Türen selbst öffnen.

Boguslaw Schaeffer

Folianten

Les foliants sont une extension de la „notation graphique“ développée dans les années cinquante (exemples dans les oeuvres de Earle Brown, Sylvano Bussotti, Cornelius Cardew): und extension en trois dimensions, utilisant plus largement la couleur, aussi que des materiaux transparents déplacables (introduits par John Cage dan „Variations I“, en 1958). La tri-dimensionalité et le déplacement des matériaux sont décicifs. La première parce qu’elle permet permet à ces pièces d’exister en principe indépendamment de toute notion de notation musicale apprise (signes et images sur une surface plane pouvant être représentés par leurs coordonnées verticales et horizontales); le second parce qu’il permet à la notation plastique du mobile d’être appliquée à la transformation musicale (dans son aspect de notation). Aussi indépendantes que puissent être ces pièces comme objets plastiques, visuels, leur imagerie comporte beaucoup d’inspiration musicale, incorporant des parties d’instruments de musique, s’identifiant par le nom d’instruments spécifiques et incluant parfois des éléments de notation musicale traditionelle. Ce sont des représantions élégantes et évocatrices du matériaux musical. Elle sont aussi concues pour une utilisation musicale, c’est à dire pour produire de la musique. Comme telles, elles soulèvent des questions intéressantes sur la relation entre notation musicale et exécution. Par exemple, comment la profondeur de champ (la dimension ajoutée) peut-elle être interprétée en termes de musique? Littéralement (la localisation dans l’espances des sources sonores) ou figuralement (une densité variable des sons)? Ou bien, qu’elle est la relation entre le déroulement du temps, l’existence linéaire du son et l’espace? Dans quelle sens une structure formelle visuelle définie détermine-t-elle une structure acoustique définie? Si une belle pièce musicale peut être mise en notes par un graphique laid, qu’elle

fonction musicale peut avoir une notation visuellement suggestive et travaillée? Quelle est la relation entre la permanence de l’objet (notation) et l’évanescence de la musique? Est-ce-que les implications musicales des objets (la mobilité et la fragilité du mouvement dans le temps) leurs confirment quelque chose comme une âme musicale, un instrument didactique et memnonique; elle a servi de point de repère et de créatrice dans une certaine sorte d’histoire. Les foliants sont paradoxalement, une notation comme anticipation est en même temps un encouragement à une pratique musicale en quelque sorte liberée de l’histoire.

(traduction par Etienne Delmas) Christian Wolff

L’art est mobile. Il suffit seulement de vouloir le bouger.

Les foliants montre ceci clairement. Ils présentent des proportions qui cachent plus en elles que ce qu’en peut observer par le trou de la serrure. Nous pouvons aussi naturellement observer un paysage par le trou d’une serrure et il peut aussi nous

plaire. Mais ce n’est pas ainsi que l’on apprend à connaître la grande étendue. L’exemple des foliants peut nous enseigner que nous apprenons plus lorsque nous ignorons les trous de serrure des expériences commodes et qu’à la place nous

ouvrons nous-mêmes les portes.

(texte francais par Catherine Raoult) Boguslaw Schaeffer

A

fonction musicale peut avoir une notation visuellement suggestive et travaillée? Quelle est la relation entre la permanence de l’objet (notation) et l’évanescence de la musique? Est-ce-que les implications musicales des objets (la mobilité et la fragilité du mouvement dans le temps) leurs confirment quelque chose comme une âme musicale, un instrument didactique et memnonique; elle a servi de point de repère et de créatrice dans une certaine sorte d’histoire. Les foliants sont paradoxalement, une notation comme anticipation est en même temps un encouragement à une pratique musicale en quelque sorte liberée de l’histoire.

(traduction par Etienne Delmas) Christian Wolff

L’art est mobile. Il suffit seulement de vouloir le bouger.

Les foliants montre ceci clairement. Ils présentent des proportions qui cachent plus en elles que ce qu’en peut observer par le trou de la serrure. Nous pouvons aussi naturellement observer un paysage par le trou d’une serrure et il peut aussi nous

plaire. Mais ce n’est pas ainsi que l’on apprend à connaître la grande étendue. L’exemple des foliants peut nous enseigner que nous apprenons plus lorsque nous ignorons les trous de serrure des expériences commodes et qu’à la place nous

ouvrons nous-mêmes les portes.

(texte francais par Catherine Raoult) Boguslaw Schaeffer

A

The "foliants" are an extension of „graphic notation“ as developed in the 1950s

(exemplary instances in the work of Earle Brown, Sylvano Bussotti, Cornelius Cardew): an extension into three dimensions, with a far wider use of colour and a variant use of shiftable transparent materials (introduced by John Cage in „Variations I“ in 1958). The three-dimensionality and the shifting are crucial. The former because it enables these works to exist in principle indepently of any recieved notion of musical notation (marks and images on a flat surface which can be graphed by vertical and horizontal coordinates). The latter because it allows a sculptural notion of mobile to be applied to musical tranformation (in the aspect of notation). Present and independent as these works may be as visual and sculptural objects, their imagery includes much that is musical, incorporating parts of musical instruments, verbally identified by the names of specific instruments and including sometimes elements of actual musical notation. They are evocative and elegant representations of musical material. And they are also intended for musical use, that is to produce music. As such they raise interesting questions about the relation of notation to musical performance. For example, how is depth-of-field (the added dimesion) translatable into musical terms? Literally (say, location in space of sound sources) or figuratively (say, a variable density of sound)? Or, what is the relation of the time-bound, linear existence of sound to space? In what sense does a visually defined formal structure determine an acoustically defined structure?

If musically fine work might be notates in a graphically ugly way, what musical function might a visually suggestive and beautiful notation have? What is the relation of the notational object’s permanence and the music’s evanescence? Can the musical implication (say, the mobility and fragility of movement in time) of these artifacts endow them with something like a musical soul, as it were, un-freeze, de-reify them? Notation began as a recording after the fact of musical practice, as a didactic and memnonic instrument, and it has served as a marker and creator of (a certain kind of) history. The foliants are, paradoxically, notation as anticipation and at the same time inducement to a musical practice somewhat released from history.

Christian Wolff

Art is flexible, if only someone is ready to flex it. The foliants demonstrate this. They reveal more than can be glimpsed through a keyhole. Of course we can also look at a landscape through a keyhole – and even enjoy it. But that is not how we get to know the big wide world. The foliants show us that ignoring the keyholes pf experience and opening wide the doords instead will teach us more. It is up to us to comprehend this freedom.

Boguslaw Schaeffer (translated by Rana Syed/Peter Corser)

(exemplary instances in the work of Earle Brown, Sylvano Bussotti, Cornelius Cardew): an extension into three dimensions, with a far wider use of colour and a variant use of shiftable transparent materials (introduced by John Cage in „Variations I“ in 1958). The three-dimensionality and the shifting are crucial. The former because it enables these works to exist in principle indepently of any recieved notion of musical notation (marks and images on a flat surface which can be graphed by vertical and horizontal coordinates). The latter because it allows a sculptural notion of mobile to be applied to musical tranformation (in the aspect of notation). Present and independent as these works may be as visual and sculptural objects, their imagery includes much that is musical, incorporating parts of musical instruments, verbally identified by the names of specific instruments and including sometimes elements of actual musical notation. They are evocative and elegant representations of musical material. And they are also intended for musical use, that is to produce music. As such they raise interesting questions about the relation of notation to musical performance. For example, how is depth-of-field (the added dimesion) translatable into musical terms? Literally (say, location in space of sound sources) or figuratively (say, a variable density of sound)? Or, what is the relation of the time-bound, linear existence of sound to space? In what sense does a visually defined formal structure determine an acoustically defined structure?

If musically fine work might be notates in a graphically ugly way, what musical function might a visually suggestive and beautiful notation have? What is the relation of the notational object’s permanence and the music’s evanescence? Can the musical implication (say, the mobility and fragility of movement in time) of these artifacts endow them with something like a musical soul, as it were, un-freeze, de-reify them? Notation began as a recording after the fact of musical practice, as a didactic and memnonic instrument, and it has served as a marker and creator of (a certain kind of) history. The foliants are, paradoxically, notation as anticipation and at the same time inducement to a musical practice somewhat released from history.

Christian Wolff

Art is flexible, if only someone is ready to flex it. The foliants demonstrate this. They reveal more than can be glimpsed through a keyhole. Of course we can also look at a landscape through a keyhole – and even enjoy it. But that is not how we get to know the big wide world. The foliants show us that ignoring the keyholes pf experience and opening wide the doords instead will teach us more. It is up to us to comprehend this freedom.

Boguslaw Schaeffer (translated by Rana Syed/Peter Corser)

Foliant 29 - für Kontrabass

(Klangbeispiel)

(Klangbeispiel)

Foliant 33 (2014) für Schlagzeug | UA 4.11.2014 "Unerhörte Musik", Berlin | Alexandros Giovanos, Schlagzeug